Categories more

- Adventures (17)

- Arts / Collectables (15)

- Automotive (37)

- Aviation (11)

- Bath, Body, & Health (77)

- Children (6)

- Cigars / Spirits (32)

- Cuisine (16)

- Design/Architecture (22)

- Electronics (13)

- Entertainment (4)

- Event Planning (5)

- Fashion (46)

- Finance (9)

- Gifts / Misc (6)

- Home Decor (45)

- Jewelry (41)

- Pets (3)

- Philanthropy (1)

- Real Estate (16)

- Services (23)

- Sports / Golf (14)

- Vacation / Travel (60)

- Watches / Pens (15)

- Wines / Vines (24)

- Yachting / Boating (17)

Published

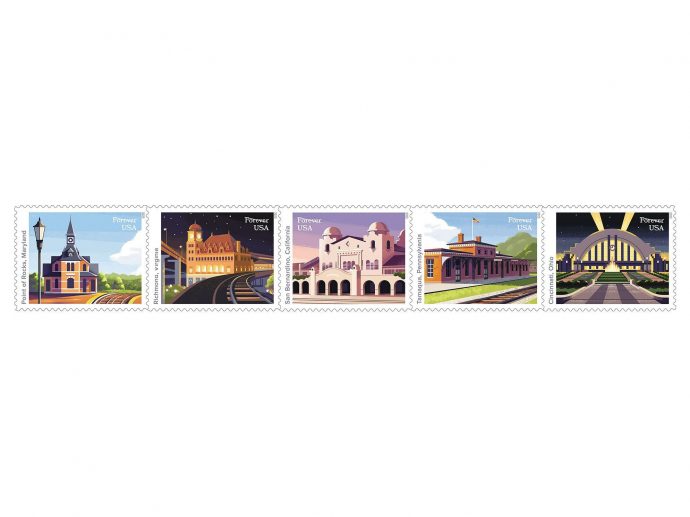

03/23/2023 by U.S. Postal ServiceTrain stations have long been gateways to exciting journeys, business travel and even mail transportation at one time across our land. The Postal Service celebrates the history, nostalgia and romance of train travel with its Railroad Stations Forever stamps.

A dedication ceremony for the stamps was held at the spectacular art deco Cincinnati Union Terminal today. News of the stamps is being shared with the hashtag RailroadStationsStamps.

"We are fortunate to be in this awe-inspiring building, the Cincinnati Union Terminal, one of the five incredible train stations to be featured in the stamp series we are dedicating today," said Dan Tangherlini, a member of the USPS Board of Governors, who served as the dedicating official. "This train station and the others on these stamps provide a majestic and significant history about these buildings that has led to their preservation, reactivation and reuse. All five stations have stories of persistence and sub-plots involving dedicated people working to save them."

America was still in its infancy when rail transportation became a feasible proposition in the mid-1820s. In the following decades, new railroad companies rushed to lay tracks across the continent, bringing the possibility of prosperity to the areas they traversed and oblivion to those they bypassed. Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, railroads were the only practical means of traveling over any significant distances; almost everybody rode the trains.

The first station buildings went up in the early 1830s. A station often was designed to advertise the importance of the surrounding community, along with the power and prestige of the railroad company serving it. In many smaller towns, the railroad station was the focal point of community life.

Noteworthy stations began brightening the American landscape by the 1870s and, although many fell to the wrecking ball once they had outlived their original purpose, hundreds survived. These new stamps feature five architectural gems that continue to play an important role in their community.

It is often due to the persistence of historic preservationists that our great railroad stations have survived. All five of those featured on these stamps are listed in the U.S. Department of the Interior's National Register of Historic Places.

Five Railroad Stations that Helped Bind the Nation

The spectacular art deco Union Terminal opened in Cincinnati at the height of the Great Depression, in early 1933. The Ohio municipality had become an industrial and commercial center by 1900, as well as the country's 10th largest city and a major gateway and transfer point for rail passengers traveling between much of the Midwest and the South. The New York architectural team of Alfred T. Fellheimer and Steward Wagner devised a design that mirrored the prosperity and optimism of the 1920s: a monumental half-dome rising from an enormous, raised plaza, with interior mosaics celebrating the city's important industries. However, soon after construction kicked off in August 1929, Wall Street crashed. Union Terminal would be among the last great train stations built during the railroad era.

Designed for 216 trains per day, the station was welcoming just a handful by the time passenger service ended altogether in 1972. The city renovated and reopened it in 1990 as the Cincinnati Museum Center, and the next year Amtrak restored passenger rail service there.

"It's an incredible honor for our historic Union Terminal to be immortalized on a U.S. postage stamp. Its history and architecture make it a National Historic Landmark, but its place in people's lives make it an icon," said Elizabeth Pierce, president and CEO of the Cincinnati Museum Center at historic Union Terminal. "Union Terminal has been an integral part of our community's memories for nine decades and with the release of these commemorative stamps, we get to reintroduce the nation to our local treasure."

Pennsylvania's Tamaqua Station, built by the Philadelphia & Reading Railroad, opened in 1874, replacing a wood-frame depot that had burned down. It was thanks to the railroad, which first arrived in Tamaqua in 1831, that the town had emerged as an anthracite coal center and regional hub. The new station's Italianate elegance underscored this. Residents and visitors alike enjoyed the station's restaurant, along with the manicured garden and fountain at Depot Square Park in front of the building.

Tamaqua peaked as an anthracite center by 1920. Its fortunes waned as other types of fuel reduced the use of anthracite coal. The park closed in 1950 and the land was redeveloped. The railroad began cutting passenger train service to Tamaqua and then ended it completely in 1963, converting the station to administrative use before shuttering it in 1980. After a fire the following year, a historic preservation group successfully campaigned to save the building, purchasing it in 1992 and restoring it by 2004. A re-created Depot Square Park was dedicated the same year. The station has since housed a heritage center, shops and a restaurant, and the Reading and Northern Railroad now operates an occasional tourist train that stops at Tamaqua.

The Gothic Revival Point of Rocks Station, in rural but suburbanizing Frederick County, MD, stands at a crossroads. It was built on the spot where the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad's Metropolitan Branch, to Washington, D.C., split from the original main line, which ran between Baltimore and the Midwest.

Founded in 1827 as the country's first long-distance freight and passenger railroad, the B&O reached Point of Rocks in 1832. Forty-one years later, the company opened the Metropolitan Branch. It hired Baltimore architect E. Francis Baldwin to design a new headquarters building in Baltimore, as well as the Point of Rocks station, completed in 1875, and numerous other notable stations.

The Metropolitan Branch eventually became the B&O's main line for passenger and freight trains to and from Baltimore, Washington and other points. While the Point of Rocks station building closed in 1962, trains continued to stop there to take on and drop off passengers.

In 1971 Congress consolidated 20 long-distance passenger lines into the National Railroad Passenger Corp., or Amtrak. Point of Rocks became a commuter stop only, served by the B&O until the Maryland Area Regional Commuter (MARC) rail line took over in the mid-1980s and expanded service. The station building now houses offices for CSX Transportation, the successor to B&O's freight service.

Main Street Station, in Richmond, VA, calls to mind a French chateau, but one embraced by train tracks and a highway. Built by two of the railroads that once served the city — the east-west Chesapeake and Ohio and the north-south Seaboard Air Line — it opened in 1901 in a busy commercial district at the edge of downtown. The Philadelphia firm of Wilson, Harris and Richards, specialists in railroad architecture, chose the Second Renaissance Revival style for the ornate building, giving it a steep roof and a six-story clock tower.

In the 1950s, the construction of the elevated interstate highway, nearly touching the station, made plain the automobile's ascendancy. Yet both rail transportation and the station survived. Amtrak took over passenger service there in 1971 before moving to a new, suburban depot four years later. Main Street Station subsequently underwent major renovations and revival, briefly in the 1980s, as a shopping mall and then office space. Amtrak returned in 2003 and now shares the building, which received another massive makeover about 2017, with a visitors center and grand event space.

When the Santa Fe Depot opened in San Bernardino, CA, in 1918, it was advertised as the largest railroad station west of the Mississippi River. The Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad had arrived in San Bernardino in 1886 and built a wood-frame station. After a fire destroyed the structure in 1916, company architect W.H. Mohr designed its replacement in the Mission Revival style, adding Moorish elements.

Into the 1950s, the San Bernardino depot served as an important gateway for thousands of Americans migrating to California, especially from Midwestern and Southern states. It also served as an employment center for the large proportion of the area's population that worked in railroad-related jobs.

The Santa Fe Railroad turned its passenger service over to Amtrak in 1972. Two decades later the San Bernardino Associated Governments bought the old station and added Metrolink commuter rail service. Since the completion of extensive renovations in the early 2000s, the San Bernardino Depot has also housed local government offices as well as a history and railroad museum.

Just as the railroad represents progress and movement, railroad stations hold stories: of industry and commerce, of migration and hope for the future, of reunions and goodbyes. They are gateways, and crossroads where lives meet. The Postal Service is proud to honor these five historic American railroad stations.

Derry Noyes, a USPS art director, was art director for the project. Down the Street Designs was responsible for the digital illustrations, typography and overall design of the pane.

Railroad Stations Forever stamps will be issued in panes of 20.