Categories more

- Adventures (17)

- Arts / Collectables (15)

- Automotive (37)

- Aviation (11)

- Bath, Body, & Health (77)

- Children (6)

- Cigars / Spirits (32)

- Cuisine (16)

- Design/Architecture (22)

- Electronics (13)

- Entertainment (4)

- Event Planning (5)

- Fashion (46)

- Finance (9)

- Gifts / Misc (6)

- Home Decor (45)

- Jewelry (41)

- Pets (3)

- Philanthropy (1)

- Real Estate (16)

- Services (23)

- Sports / Golf (14)

- Vacation / Travel (60)

- Watches / Pens (15)

- Wines / Vines (24)

- Yachting / Boating (17)

Published

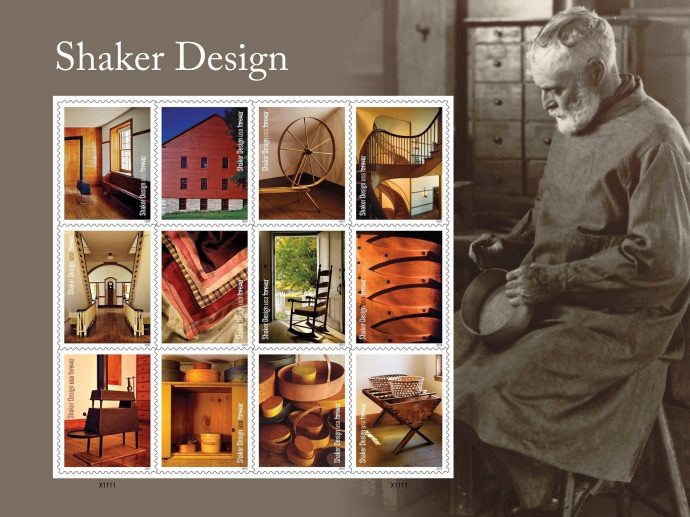

07/05/2024 by U.S. Postal ServiceThe U.S. Postal Service today revealed the refined, timeless beauty of Shaker design with 12 new stamps, in honor of the 250th anniversary of the arrival of the first Shakers in America.

Attendees at the Shaker Hancock Village explored the collection of furniture, crafts and tools, and had the opportunity to see four of the Shaker designs used in the stamp images.

News of the stamps is being shared with the hashtag ShakerDesignStamps.

Devoutly religious and committed to simple living, the Shakers imbued everything they made with uncommon grace — from modest oval boxes to furniture, textiles and even architecture. Their minimalist designs include no excessive ornamentation. Instead, the Shakers concentrated on the harmony of form and function, creating pieces renowned worldwide for their simplicity, utility and impeccable quality.

Founded in England in the 18th century, the Shakers were a celibate, pacifist and socially progressive offshoot of mainstream Quakerism. Calling themselves the United Society of Believers in Christ's Second Appearing, they were persecuted for their beliefs and practices, most notably ecstatic dancing during worship. In 1774, a small group of Shakers immigrated to America and eventually settled near Albany, NY. By the 1840s, at their height, approximately 5,000 Shakers lived in more than a dozen, largely self-sufficient settlements from Maine to Kentucky. They arranged their communities in "families," where men and women lived as brothers and sisters, property was held in common, and everyone aspired to create heaven on earth.

Shaker design exemplifies some of the core values of Shaker life: honesty, humility and joyful simplicity. Viewing all work as a form of worship, the Shakers found God in the details of everything they made and so they aspired to nothing short of perfection. "Do all your work as though you had a thousand years to live," urged Shaker leader Ann Lee, "and as you would if you knew you must die tomorrow." In stripping objects of all but their essential elements, the Shakers not only exposed the elegance inherent in even the most humble of items but also reinvented the concept of beauty itself.

With its emphasis on durability, functionality and timeless minimalism, Shaker design has had a profound effect on generations of architects, artisans and crafters. Today, Sabbathday Lake in Maine remains the only active Shaker village in the world. Other settlements operate as living history museums, where visitors can see authentic Shaker design and experience the Shaker way of life in person.

Stamp Design

The 12 Shaker Design stamps feature photographs by Michael Freeman and are arranged in three rows of four stamps each.

Row 1 (left to right)

Meeting room, Brick Dwelling, Hancock Shaker Village, Pittsfield, MA

The meeting room showcases quintessential elements of Shaker design, including built-in cupboards, a peg rail for keeping items off the floor, a long communal bench, and a cast-iron wood-burning stove.

Tannery, Shaker village of Mount Lebanon, New Lebanon, NY

Founded in 1787, Mount Lebanon served as a model and leader for all other Shaker communities. The tannery, which was built in 1834, highlights the simple symmetry of Shaker architecture.

Spinning wheel, Fruitlands Museum, Harvard, MA

Like everything the Shakers made, this spinning wheel has a simplified and unadorned form that perfectly highlights its function without sacrificing visual appeal.

Staircases, Trustees' Office and Guest House, Shaker Village of Pleasant Hill, Harrodsburg, KY

Rising three stories and bathed in light, the staircases, which were built in 1839-1841, display Shaker design at its height, their organic form offering a pleasing contrast to the straight lines of the peg rails.

Row 2 (left to right)

Dwelling house hallway, South Union Shaker Village, Auburn, KY

All Shaker dwellings had two staircases, one for men and one for women.

Silk neckerchiefs, South Union Shaker Village, Auburn, KY

The Kentucky Shakers were among the first in the United States to raise silkworms and weave silk into cloth. These brightly colored neckerchiefs were worn over the shoulders to protect clothing and preserve modesty.

Rocking chair, Canterbury Shaker Village, Canterbury, NH

Chairs like this rocker were used by community members and also sold to the "world," as the Shakers called mainstream society. It features back slats that increase in size from the seat to the top of the chair and are bent just slightly to accommodate the sitter more comfortably.

Bentwood box detail, Hancock Shaker Village, Pittsfield

"Swallowtail" joints allowed the side of a wooden box to expand and contract without buckling or cracking. The joints were secured with copper tacks, which would not rust and discolor the wood.

Row 3 (left to right)

Heater stove, Hancock Shaker Village, Pittsfield

The Shakers discovered that a cast-iron wood-burning stove could heat a room more efficiently than a fireplace. The additional box on top, called a "super heater," increased the surface area, allowing the stove to give off more heat with the same amount of wood. By enclosing the flames, the stove also decreased the threat of fire.

Cupboard with oval boxes, Fruitlands Museum, Harvard

Because their beliefs stressed cleanliness and order, the Shakers made abundant cupboards and cabinets to keep everyday objects organized, out of sight and free of dust.

Bentwood boxes and carriers, Fruitlands Museum, Harvard

The Shakers made their iconic bentwood boxes in a variety of shapes and sizes. Some were finished with a lid, while others featured a handle to make carrying items easier.

Cheese baskets, Hancock Shaker Village, Pittsfield

Dairy farming was an important aspect of life in some Shaker villages. Featuring a large, hexagonal woven pattern, cheese baskets were lined with cheesecloth in order to separate the curds and whey.

Derry Noyes served as art director and designer for the stamp pane.

Shaker Design stamps are being issued in panes of 12 as Forever stamps, which are always equal in value to the current First-Class Mail one-ounce price.