Categories more

- Adventures (17)

- Arts / Collectables (15)

- Automotive (37)

- Aviation (11)

- Bath, Body, & Health (77)

- Children (6)

- Cigars / Spirits (32)

- Cuisine (16)

- Design/Architecture (22)

- Electronics (13)

- Entertainment (4)

- Event Planning (5)

- Fashion (46)

- Finance (9)

- Gifts / Misc (6)

- Home Decor (45)

- Jewelry (41)

- Pets (3)

- Philanthropy (1)

- Real Estate (16)

- Services (23)

- Sports / Golf (14)

- Vacation / Travel (60)

- Watches / Pens (15)

- Wines / Vines (24)

- Yachting / Boating (17)

Published

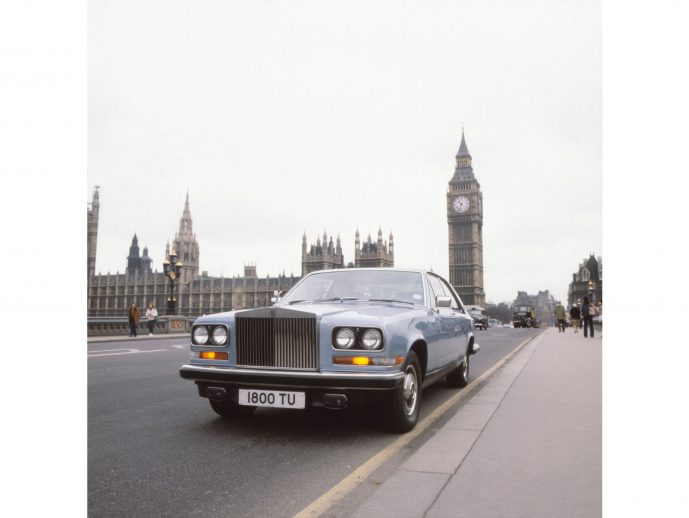

01/03/2025 by Rolls-Royce Motor Cars“Of all the Rolls-Royce models in this series, perhaps none is as distinctive as Camargue, whose design still provokes vigorous debate among car enthusiasts half a century after its launch. While its aesthetics remain a matter of personal taste, Camargue’s importance and place in the Rolls-Royce story are indisputable. Designed in collaboration with the legendary Italian house Pininfarina, it upheld the marque’s long tradition of continuous improvement over its predecessors in engineering, technology, performance and levels of comfort. It was also the first Rolls-Royce to be designed with safety in mind from the ground up. Though never built in large numbers, it was a great export success; today, its rarity and design, which for many perfectly capture the essence of the 1970s, make it a true modern classic and increasingly desirable with collectors.”

Andrew Ball, Head of Corporate Relations and Heritage, Rolls-Royce Motor Cars

In 1966, Rolls-Royce launched a two-door saloon version of Silver Shadow, built by its in-house coachbuilders, Mulliner Park Ward. By 1969, the company was starting to think about its potential replacement and senior management felt the new design needed to be ‘dramatically different’ from the existing product line-up.

In October of that year, a Mulliner Park Ward saloon was sent to the Turin headquarters of legendary coachbuilder Pininfarina. Collaborating outside the Rolls-Royce design team was a radical departure from the usual process, but the two companies had collaborated before; Managing Director Sir David Plastow later recalled that Rolls-Royce had found Pininfarina easy to work with because “they understood the Rolls-Royce culture”.

Pininfarina duly dismantled the car, using its floorpan as the basis for the new model. (In the event, it would be produced alongside the Mulliner Park Ward car, rather than replacing it.) Though no driver, occupant or observer would have been aware of it, the new design marked an interesting historical inflection point as the first Rolls-Royce ever to be built entirely using metric, rather than imperial measurements.

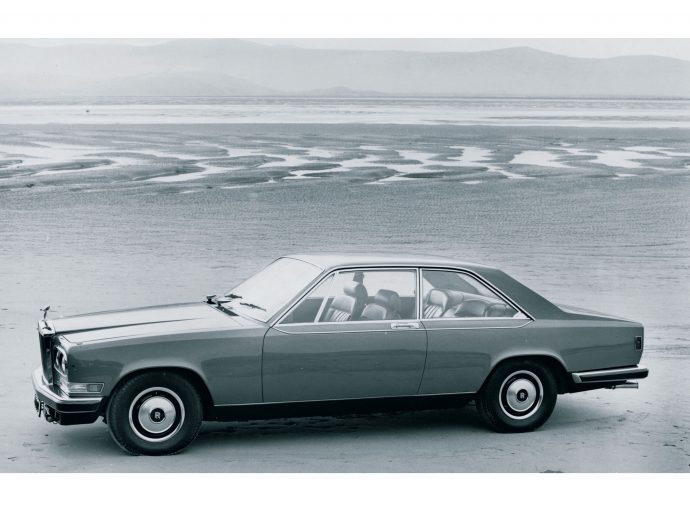

Sergio Pininfarina assigned the project to his Chief of Styling, Paolo Martin, whose portfolio included the Ferrari Dino Berlinetta Competizione concept car for the 1967 Frankfurt Motor Show. In a precise and detailed brief that, happily, has been preserved for posterity, Martin and his team were tasked with creating “a modern and stylish motor car for the owner driver which maintains the traditional Rolls-Royce features of elegance and refinement. The principal styling features are a long-line shape with sharp edge surfaces well-matched to the classic shape of the Rolls-Royce radiator. A reduction in height compared to the Silver Shadow and an increase in width, a very inclined windscreen, a large area of glass, and the use of curved side windows for the first time on a Rolls-Royce.”

Pininfarina did not present Rolls-Royce with a fait accompli, but worked closely with the marque’s own designers. Together, they produced a final design in which, as they explained, “the impression of lightness and slenderness has been achieved by the careful shaping of panels rather than using chromium-plated decoration. The external trimmings and light units are simple in design and modest in dimensions. The interior concept is very modern, functional like an aircraft cockpit and equipped with several high-precision instruments. The location of switches and controls has been designed to be easily found, distinctive and precise in use.

“The two objectives of modern design and functionality have been achieved without giving up the most traditional and distinctive Rolls-Royce items.” These items included the Pantheon Grille, which was retained in its conventional form but with the top edge daringly tilted forward by four degrees. This immediately became one of the motor car’s most recognisable – and controversial – visual signifiers; it would be the only factory-built Rolls-Royce ever to display this subtle but arresting deviation from the vertical.

For Mulliner Park Ward, the new model was a crucial test. This would be the first entirely new production model since Rolls-Royce had been split into separate automotive and aerospace businesses in 1971, and it was understandably keen to prove its capabilities. The first prototype, codenamed ‘Delta’, was on the road by July 1972; after almost three years in development, the new motor car was presented to the world in March 1975.

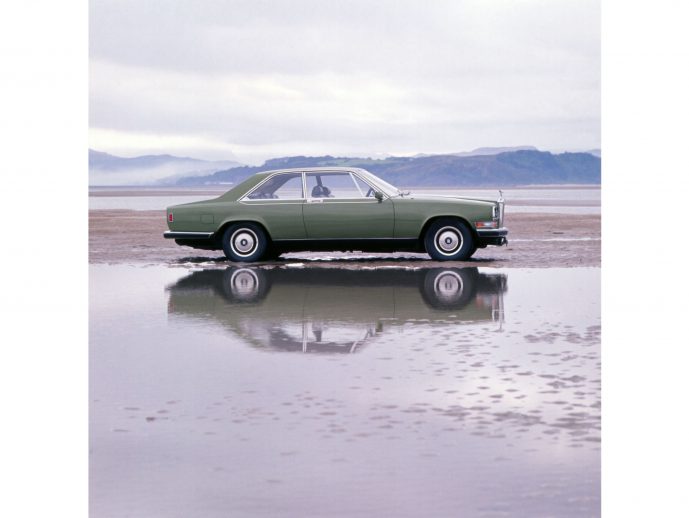

From a shortlist of two possible names, Corinthian and Camargue, the company had wisely chosen the latter. Like its companion model Corniche, Camargue’s name was inspired by the marque’s longstanding connections to the south of France, where Sir Henry Royce had overwintered every year from 1917 until his death in 1933. The Camargue itself is an extensive coastal plain between the Mediterranean and the two arms of the Rhône river delta, south of the city of Arles where Vincent Van Gogh and Paul Gauguin set up their studio in the ‘Yellow House’ in 1888. Made up of large saltwater lagoons, or étangs, surrounded by reedbeds and marshes, the region is internationally renowned for its birdlife, and the white (properly called grey) Camarguais horses and their colourful riders, the gardians.

For the Camargue press launch, held in Catania, Sicily, Rolls-Royce produced a set of nine motor cars, including chassis JRH16648 finished in Mistletoe Green. This example was used by the Rolls-Royce marketing department until September that year, when it was sold to a private client via London dealer Jack Barclay; it was later modified to left-hand drive.

Camargue’s dramatic yet elegant design included wide doors that, according to the sales brochure, “make possible an ease of entry not usually available on two-door motor cars” with “the backrest to the front seat unlocked electrically at the touch of a button, to give an access to the rear compartment which has a seat of exceptional comfort and width, allowing excellent visibility”.

The interior was particularly striking, featuring the first use of a brand-new, ultra-soft leather called ‘Nuella’. In accordance with Pininfarina’s ‘aircraft cockpit’ concept, the fascia featured switchgear and round instrument dials housed in matt-black rectangular surrounds, giving a sleek, aeronautical look. A pleated roof lining and seats set lower in the body than those on the Silver Shadow gave excellent headroom, while the rear-seat legroom was vast for a two-door coupé. All occupants benefitted from the first comprehensive dual-level air conditioning system ever fitted to a Rolls-Royce motor car.

Like every new Rolls-Royce model, Camargue represented the most advanced automotive engineering of its time and was the product of the marque’s policy of constant refinement, established by Henry Royce himself. Power came from an aluminium, 6.75-litre V8 engine with a three-speed automatic transmission; a chassis equipped with fully independent suspension and automatic height control ensured the marque’s fabled Magic Carpet Ride. It therefore offered significantly enhanced performance, safety and comfort, reflected in the fact that it was nearly twice the price of the Silver Shadow.

While Pininfarina had given Camargue an ‘exceptional grace and beauty’, there was great substance beneath the style. This was the first Rolls-Royce to be designed from the outset to meet the increasingly stringent safety standards being introduced worldwide at this time, with enhanced crash-deformity resilience, energy-absorbing interior materials and seatbelts for all four seats. The bodyshell itself was so strong that the American safety tests for side impact, rear impact, roof impact and a frontal 30mph collision were all conducted on – and passed by – the same car.

For the first three years, Camargue was built in north London at the Mulliner Park Ward works on Hythe Road in Willesden; in 1978, production moved to the Rolls-Royce factory in Crewe, and continued until 1987. With only 529 examples sold over 12 years, Camargue stands as a testament to exclusivity – its rarity makes it a sought-after treasure among collectors today. Sales proved most notable in the USA which accounted for almost 75% of its lifetime sales.

Managing Director David Plastow, whose background was in marketing, saw a motor car as “an exciting, dramatic purchase which said something about the character of the person who bought it”. With its distinctive styling, Camargue certainly allowed its owner to make a bold statement. Though its aesthetics are still keenly debated even today, it remains one of the most instantly recognisable Rolls-Royce models, beloved by the generation that first knew it, and an increasingly desirable modern classic among collectors and enthusiasts.