Categories more

- Adventures (17)

- Arts / Collectables (15)

- Automotive (37)

- Aviation (11)

- Bath, Body, & Health (77)

- Children (6)

- Cigars / Spirits (32)

- Cuisine (16)

- Design/Architecture (22)

- Electronics (13)

- Entertainment (4)

- Event Planning (5)

- Fashion (46)

- Finance (9)

- Gifts / Misc (6)

- Home Decor (45)

- Jewelry (41)

- Pets (3)

- Philanthropy (1)

- Real Estate (16)

- Services (23)

- Sports / Golf (14)

- Vacation / Travel (60)

- Watches / Pens (15)

- Wines / Vines (24)

- Yachting / Boating (17)

Published

10/27/2024 by Rolls-Royce Motor Cars“Claude Johnson is celebrated by posterity as ‘the hyphen in Rolls-Royce’; it is typical of the man that this is a title he gave himself. But if anything, it understates the importance and influence of ‘CJ’, as he was universally known, in the marque’s first two decades and beyond. A natural showman with a genius for generating publicity – for himself, as well as the company – his ideas, energy and personality matched his imposing physical stature. He brought an extraordinary mix of skills, talents, experience and personal qualities to his role as the company’s first Commercial Managing Director: a truly fascinating, larger-than-life character with a colourful background who achieved remarkable things.”

Andrew Ball, Head of Corporate Relations and Heritage, Rolls-Royce Motor Cars

Claude Goodman Johnson – known to all simply as ‘CJ’ – was born in Buckinghamshire on 24 October 1864, one of seven children.

From London’s St Paul’s School, Claude progressed to the Royal College of Art. Here, he met Sir Philip Cunliffe-Owen, Deputy General Superintendent of the South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria & Albert Museum), where Claude’s father worked. Through him, CJ secured his first job, as a clerk at the Imperial Institute (now Imperial College London). There, he was put to work arranging exhibitions. His debut effort, the Fisheries Exhibition, was described in W. J. Oldham’s book The Hyphen in Rolls-Royce as the ‘fashionable haunt of London for the summer of 1883’. He followed this triumph with events dedicated to Health in 1884 and Inventions the following year; by the time his Colonial and Indian Exhibition opened in 1886, CJ was managing a workforce of around 200.

But if his professional life was a model of sober industry, CJ’s personal circumstances were already somewhat more colourful. Soon after starting work at the Institute, he eloped with his girlfriend, Fanny Mary Morrison, much to the distress of both sets of parents. They had eight children, but tragically only the seventh child, Betty, survived. Eventually, the marriage failed, whereupon CJ married his long-time mistress, whom he always called ‘Mrs. Miggs’; they had a daughter known as Tink.

ON WITH THE SHOW

His private life had no discernible effect on CJ’s career trajectory. In 1895, the leading scientific author and road transport pioneer, Sir David Salomons, organised England’s first ‘Motor Exhibition’ at his home in Tunbridge Wells. The event proved only moderately successful, but caught the eye of the Prince of Wales, an enthusiast for the ‘new’ motor cars. His Royal Highness was keen to try a similar exhibition – and where better than at the Imperial Institute, which he had long championed, and who better to arrange it than the Chief Clerk, Claude Johnson?

That 1896 event, rather quaintly entitled Motors and their Appliances, proved a turning point for CJ. By July 1897, a group of enthusiasts had founded the Automobile Club of Great Britain & Ireland (later the Royal Automobile Club, or RAC), but were still looking for a full-time Secretary. Aware of his success in organising the Imperial Institute exhibition, they offered CJ the job, which he eagerly accepted.

His talents for organisation and promotion made him perfect for the role. Under his auspices, the Club held numerous motoring events for its members, including the 1000 Mile Trial run during April and May 1900, and won by a certain Charles Stewart Rolls in his Parisian-made 12 H.P. Panhard.

IN GOOD COMPANY

By 1903, CJ had almost single-handedly built the Club’s membership to around 2,000. But his restless mind was ready for a change, and when Club member Paris Singer, son of sewing machine magnate Isaac Singer, offered him a job with his City & Suburban Electric Car Company, CJ jumped at it. This, too, was only a stepping stone to what would become his life’s work. After just a few months with Singer, he joined another Club member in his fledgling car-sales business, a certain C.S. Rolls & Co., thus changing the course of history.

As business partners, the two men were ideally matched. The urbane, well-connected, Cambridge-educated engineer Rolls looked after the technical side of things (and dealt with the nobility), while CJ handled publicity and sales to less exalted patrons.

The company flourished, but Rolls was desperate to find a British-made motor car as good as the Continental models they were selling. In 1904 he found it, in a new 10 H.P. car made by Henry Royce. Following their historic first meeting in Manchester on 4 May, Rolls returned to London and informed CJ he had agreed to sell every car Royce could make under a new name, Rolls-Royce. CJ was instantly captivated by the project, and when the Rolls-Royce company was formally established in 1906, he assumed the role of Commercial Managing Director.

SUCCESS BREEDS SUCCESS

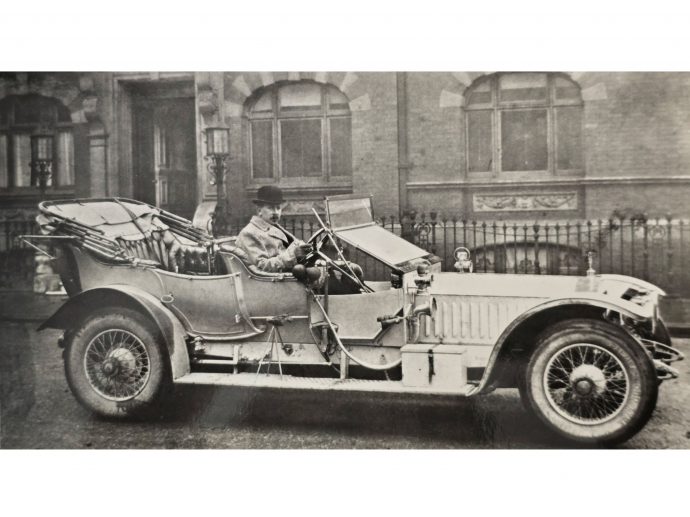

CJ’s talent and enthusiasm for publicity stunts had found its perfect outlet. In 1906, Rolls-Royce won the Scottish Reliability Trials with a 30 H.P. motor car. At CJ’s urging, Royce developed a larger, more powerful model, the 40/50 H.P. capable of carrying larger bodywork. In an inspired move, CJ dubbed the 12th example, with its silver-plated brightwork and silver paint, ‘The Silver Ghost’ and entered it in the 1907 event, which it won convincingly. A lesser person might have been satisfied, but not CJ. To underline the motor car’s reliability, he immediately arranged for it to participate in a ‘non-stop’ run – a drive without an involuntary stop on the road, apart from punctures, during a set period in the day. Travelling back and forth between London and Edinburgh (except on Sundays), they amassed nearly 15,000 miles and set a new world endurance record. Characteristically, CJ drove the first 4,000 miles himself, yet found time every day to send a postcard to his four-year-old daughter.

Less arduous but equally noteworthy PR efforts followed: placing a brimming glass of water on a running engine without spilling a drop and balancing a coin on the edge of the radiator cap without it falling over. CJ also wrote and published a successful series of guidebooks with Lord John Montagu entitled ‘Roads Made Easy’, which included the charming direction ‘FTW’, meaning ‘follow the telegraph wire by the roadside’.

It was through Montagu that CJ met the illustrator and sculptor Charles Sykes. Rightly concerned that the fad among motor car owners for fitting comical mascots to their radiator caps was spoiling the cars’ classical lines, he commissioned Sykes to design an official one. What we know today as the Spirit of Ecstasy was unveiled in 1911, and it remains one of CJ’s most important and enduring legacies. Still adorning the prow of Rolls-Royce motor cars to this day, CJ’s commission has gone on to become the marque’s timeless muse and an inspiration for countless masterpieces, including its recent Phantom Scintilla Private Collection.

A FRIEND INDEED

It would be easy to assume that the ebullient, outgoing CJ would have little in common with the serious, rather austere engineer Royce. In fact, the two were close friends, respectful of each other’s integrity; Royce’s unending desire to design the best motor car possible was perfectly complemented by CJ’s ability to keep the Rolls-Royce name firmly in the public consciousness, and the operation running smoothly.

Indeed, it’s little exaggeration to say that CJ saved Royce’s life. By 1911, years of overwork and poor diet had taken a severe toll on Royce’s health, and he fell seriously ill; after an operation, he was given just three months to live. The Derby factory was too stressful an environment, so CJ found Royce a house, at Crowborough in East Sussex.

On a convalescent trip to the South of France – travelling in CJ’s magnificent green-and-cream Barker-bodied limousine he’d named The Charmer – they stopped at CJ’s holiday home, Villa Jaune, at Le Canadel. Royce liked the place and said he could happily spend the winter months working from there. CJ immediately bought a nearby plot of land and built three houses, designed by Royce. Villa Mimosa was for Henry himself, while Le Bureau served as a design studio, and Le Rossignol – ‘the nightingale’ – was the house in which the designers lived. It was very important to Royce that the designers were close to him, so that they were able to quickly bring their respective visions to reality. Royce divided his time between England and France until his death in 1933.

CHANGING TIMES

CJ’s own capacity for work was undiminished. In 1912, he opened a sales showroom in Paris, decorated in Adam style with Louis XVI-style furniture. That same year, Silver Ghost owner James Radley started the gruelling Austrian Alpine Trial, but failed to finish. Outraged, CJ vowed to avenge this humiliation, and in 1913 entered a ‘works’ team of three cars (plus Radley as a privateer) with redesigned, four-speed gearboxes. The cars swept the board in what would be the last competitive event to be arranged by CJ. During this period, CJ also introduced the first three-year guarantee on Rolls-Royce motor cars and set up a pension scheme for the workforce.

From 1914 to 1918, Rolls-Royce focused exclusively on aero engine production – something CJ had insisted upon for both commercial and patriotic reasons. But even before hostilities ceased, he foresaw that large, complex and expensive motor cars like Silver Ghost would have limited appeal in a straitened, post-war world. He therefore proposed a smaller model that would be suitable for owner-drivers, which Royce duly delivered with the new 20 H.P. Cannily, CJ spotted that under the new Road Tax, charged at £1.00 per RAC-rated unit of horsepower, the Silver Ghost would attract a tax of £47.00 a year, but the new 20 H.P. only £20.00.

CJ made two further lasting major contributions to Rolls-Royce motor cars. First, when Royce proposed to abandon the traditional Pantheon radiator design for something more streamlined, CJ successfully persuaded him otherwise. Second, when Silver Ghost’s replacement model was ready in 1925, CJ named it after a pair of former Trials cars that were both known as Silver Phantom. He called this model New Phantom; eight generations later, what would become the most storied nameplate in the marque’s history celebrates its own centenary in 2025.

“HE WAS THE CAPTAIN; WE WERE ONLY THE CREW.”

On 6 April 1926, CJ went to his Conduit Street office as usual, despite having felt unwell and losing a noticeable amount of weight for some time. The following day he felt worse, but forced himself to attend his niece’s wedding, where he collapsed. He was driven home by his eldest daughter Betty; on the way, he told her that he felt he would not pull through, and that he wanted neither fuss nor flowers at his funeral. His death on Sunday 11 April was reported by national newspapers and the BBC, reflecting his high public profile and immense importance to Rolls-Royce. Royce was deeply distressed at his old friend’s death, saying: “He was the captain; we were only the crew.”

For all his professional elan and showmanship, CJ was personally modest and highly scrupulous. He never held shares in the company, lest he should be accused of feathering his own nest, nor did he own a Rolls-Royce motor car himself, always using a company Trials car instead. When he was offered a knighthood for Rolls-Royce’s contribution to the war effort, he declined it, saying it should be awarded to Royce (who received only an OBE). He was forever reluctant to accept praise, always directing it towards his co-workers.

A true bon viveur, CJ enjoyed the best he could afford for himself, his family and close friends. His daughter Tink described him as: “A big man in every way: 6’2”, equally broad and well-proportioned with large and most beautiful hands. His size epitomised his ideas, ideals and generosity, his outlook and enthusiasm. A wonderful father, always very well dressed.” But perhaps the best summary of this remarkable man came from his close friend, the English portrait artist Ambrose McEvoy: “A wise and kindly giant”.